The Inner Frame

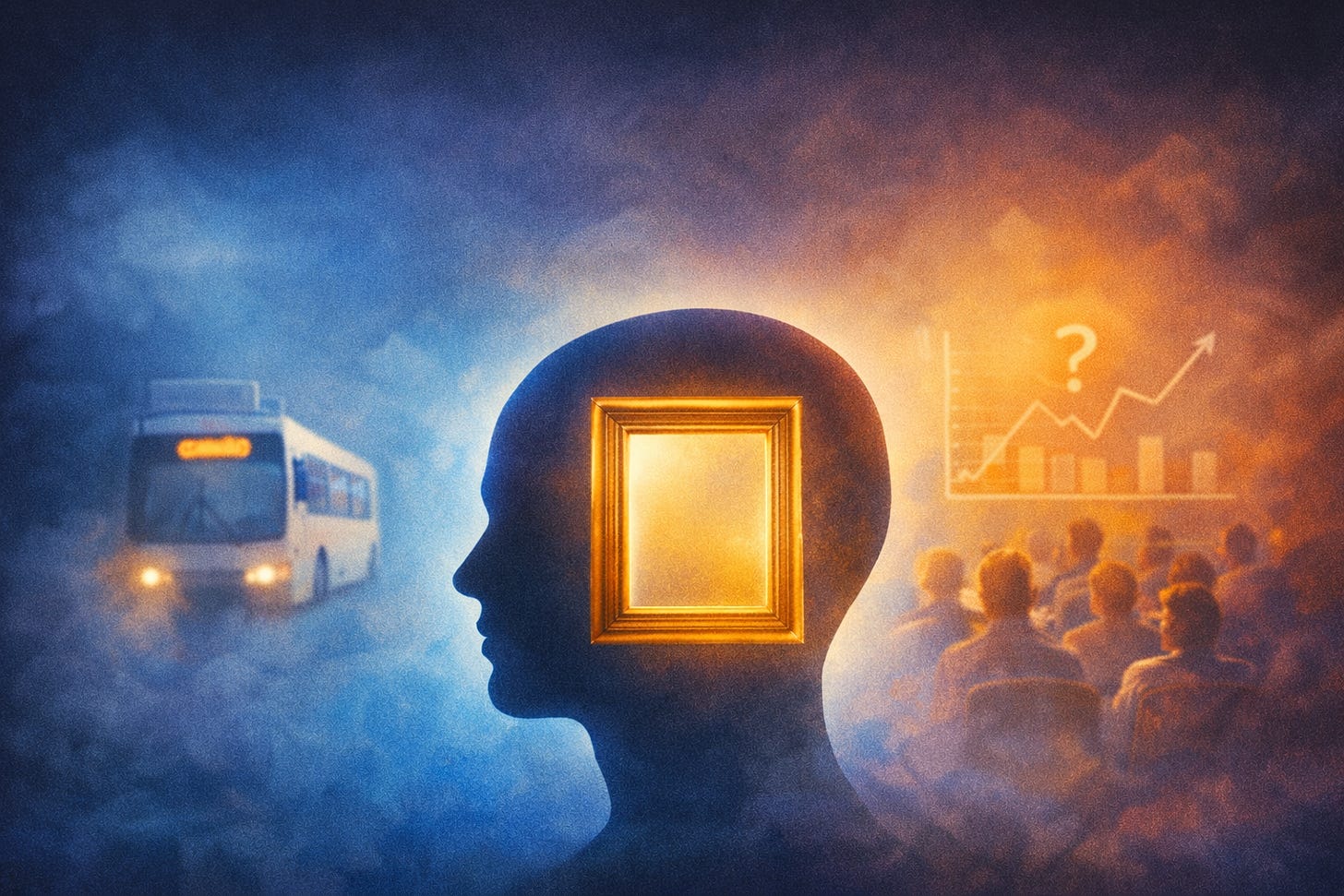

What perception, social judgment, and the future have in common when the data run thin

Many domains of experience are full of local ambiguities. This is obvious in some cases, and not so obvious in others. Among the obvious examples, there are many times when information about the world is degraded, inadequate, or forgotten, such as when listening to a conversation in a noisy room, trying to see an oncoming bus at a great distance, or walking through a dark room at night. In all these cases we rely more than usual on the inner framing factor to constrain conscious experience.

In the social realm, it is terribly important for us to know other people’s minds—their intentions, beliefs, and attitudes toward us. But we cannot read their minds directly. The evidence we have is ambiguous, and hence vulnerable to our own goals and expectations, wishes, and fears. We often make inferences about other people’s minds with a degree of confidence that is simply not justified by the evidence. In this case, inner framing factors control our experience far too often.

Political convictions show this even more graphically. A glance at the editorial pages of a newspaper shows how people with different convictions use the same events to support opposite beliefs about the world, about other people, and about morality.

Or take the domain of “the future”: Human beings are intensely concerned about the future, and we often have strong beliefs about it, even when future events are inherently probabilistic. The evidence is inadequate or ambiguous, and hence we rely more and more on internal framing constraints. These examples are fairly obvious, but there are many ambiguous domains in which we experience events with great confidence, though careful experiments show that there is much more local uncertainty than we realize. There is extensive evidence that our own bodily feelings, which we may use to infer our emotions, are often ambiguous.

Further, our own intentions and reasons for making decisions are often inaccessible to introspection, or at least ambiguous. Our memory of the past is often as poor as our ability to anticipate the future, and it is prone to be filtered through our present perspective. Historians must routinely cope with the universal tendency of people to reshape the past in light of the present, and lawyers actively employ techniques designed to make witnesses change their memory of a crime or accident. Even perceptual domains that seem stable and reliable are actually ambiguous when we isolate small pieces of information. Every corner in a normal rectangular room can be interpreted in two ways, as an outside or an inside corner. To see this, the reader can simply roll a piece of paper into a tube and look through it at any right-angled corner of the room. Every room contains both two- and three-dimensional ambiguities in its corners, much like the Necker cube and book-end illusions.

Similarly, the experienced brightness of surfaces depends upon the brightness of surrounding surfaces. Depth perception is controlled by our contextual framing assumptions about the direction of incoming light, about the shape and size of objects, and the like. These ambiguities emerge when we isolate stimuli—but it is important to note that in normal visual perception, stimulus input is often isolated. In any single eye fixation we only take in a very small, isolated patch of information. Normal detailed (foveal) vision spans only 2 degrees of arc; yet when people are asked about the size of their own detailed visual field, they often believe it must be about 180 degrees. Even the visual world, which seems so stable and reliable, is full of local ambiguities.

So here’s the practical takeaway: when the world goes locally ambiguous, notice the inner frame you’re using—because whatever you “see” next may be less a report from reality than a decision your mind is quietly making.

Fun to see Scott Adams of Dilbert fame write a whole book on how to consciously manipulate such framing for personal benefits.

Fascinating